In 2017, Moscow Authorities launched a massive renovation project, aiming to demolish over five thousand first-generation panel homes, tenderly nicknamed krushchevki after their progenitor, Nikita Krushchev. The panel homes, built in the Soviet Union between 1957 and 1971, were build as a temporary solution to a radical housing shortage. While they were most often built in neighbourhoods peripheral to the city centre, this new type of industrial construction offered central heating, separate baths and toilets, and could be erected in as few as twelve days. At a time when most Muscovites lived in crammed communal apartments, or in wooden barracks without running water, Soviet panel homes came to symbolize Soviet domesticity, represented both in official and unofficial art and literature. Yuri Pimenov painted rapidly emerging neighbourhoods in a series of oil paintings, “New Residential Quarters (1963-67),” and Antonina Romodanovskaya represented new neighbourhoods in sentimental watercolour landscapes, “My Moscow” ( The uniformity of panel homes served as crucial plot points in two seminal films valorizing Soviet domesticity, Irony of Fate (1976), and Moscow Doesn’t Believe in Tears (1980). Panel homes were well represented in underground art. Experimental writer Dmitry Prigov gave walking tours around his nondescript neighbourhood, Belaevo, and similarly, the art group, Kolektivnie Deystviya, Collective Actions, organized public performances and “AptArt” exhibitions in their crammed apartments (Tupitsyn and Tupitsyn 2017; Kiesewalter 1999), but they also organized “Trips outside the City” for communal actions—a series of art performances where, for example, an ideological banner proclaiming the victory of Communism would be hung up in an empty field outside city limits, and without any visible audience except the participants themselves.

The current plans for renovation project aim to displace over 1,5 million Muscovites (Moy Noviy Dom 2017). The municipality promises to re-house each resident into newly built high-rise apartments of equal value, and potentially, with a slightly expanded living area. However, these will no longer be five-story panel homes, but 30-40 storeys towers. My interest in the project largely builds on questions about what type of emotional responses residents may experience in the process of displacement from their former homes. These question were sparked by Muscovites’ reaction to “renovation,” which ranged from public enthusiasm, to quiet acquiescence, and to violent political protest, thus revealing an affective dimension to the experience of living in panel homes. I’m also asking how I, as an anthropologist, I can develop appropriate methods that respond to individual stories often overlooked in massive redevelopment projects. What insights could be gleaned by adopting a new set of creative methods at a time when physical fieldwork may be impossible?

Anthropologists have long been concerned with presenting collaborative, engaged scholarship in novel and accessible ways. Christopher Wright urges anthropologists to examine these modes of communication within a wider set of media practises that engage with diverse forms of creative expression (Wright 1998:21). Recently, with the proliferation of digital media, publishing models have expanded in scope and scale, and ethnographers have acknowledged that texts, mediated by notes, audiovisual records, and digital media or no longer, nor have they ever been, “neutral interpretive instruments“ (Wertsch 2001: 511). An ethnography—a monograph resulting from anthropological fieldwork, and oftentimes replete with photographs, participants’ quotes, and vivid descriptions—is also a physical (Edwards (2006:28), textured (Pinney 2003:216), biographical (Hoskins 1998), and multisensory (Marks 2008:123) object, which may allow the reader to explore the relationship between image, text, and the object’s materiality. Books, after all, our “tactile, sensory things“ (Edwards 2006:28) that have “material and sensory communicative power“ (Edwards 2006:27).

In 1993, Bernd and Hilla Becher released an artist book titled Gas Tanks. The book was a rigorous photo-document of gasholders. Each page displays spherical, spiralling, sectional structures that used to provide temporary storage of natural, coke-oven and other types of gases (Becher and Becher 1993:7). Each amongst the hundred-or-so photographic plates captured between 1963 and 1992 were taken in overcast conditions and from the same angle, rendering the subject homogeneous, distinguished mainly by type, label of location, and date. As the foreword opines:

On the subject of gas holders, the Bechers limit their remarks to a minimal functional description, leaving the esthetic dimension of their subject to the photographs themselves: much of the fascination of these photographs lies in the fact that these unadorned metallic structures, presumably built with little concern for their visual impact, are almost invariably striking in appearance (Becher and Becher 1993)

The artists have similarly explored the subjects of cooling and water towers, grain silos, coal mining pit headgears, and other industrial constructions. The artist book, in this case, allows the artists to explore formal geometry of industrial design.

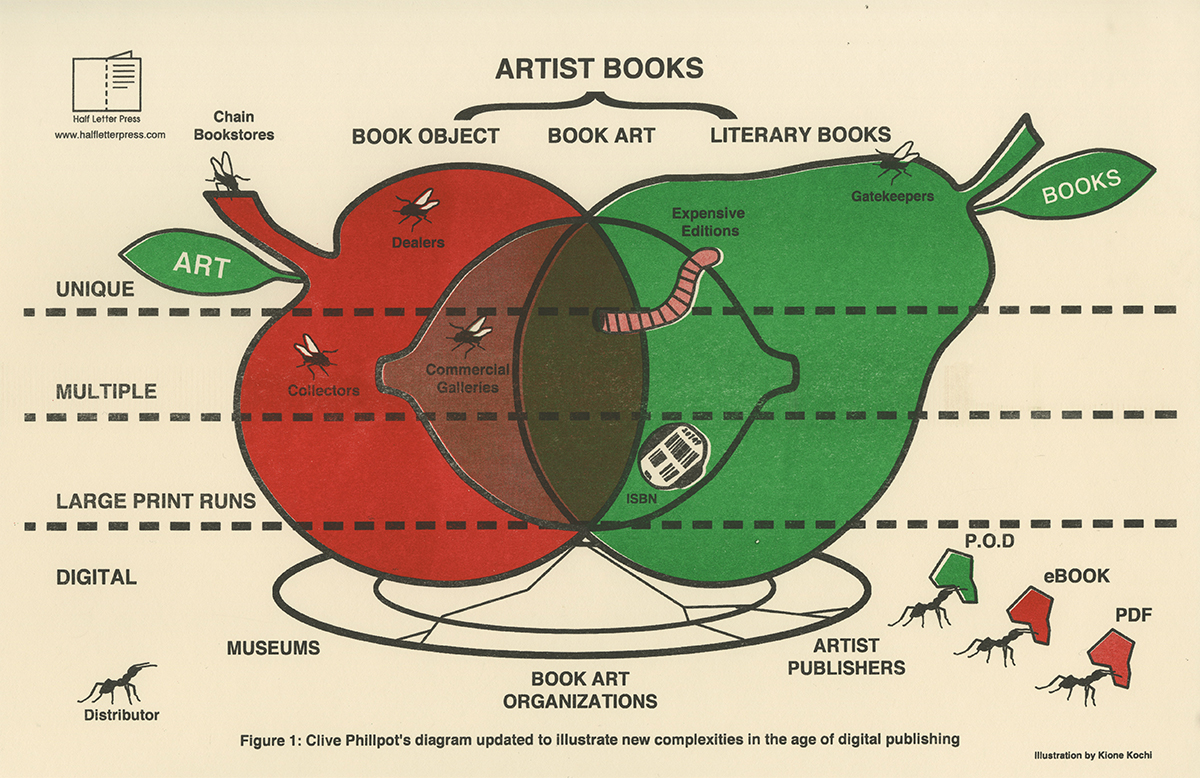

Dick Higgins admits that, “perhaps the hardest thing to do in connection with the artists book used to find the right language for discussing it“ (Higgins 1985:12). According to the author, “the making of artists’ books is not a movement. It has no program which, when accomplished, crests and dies away into the past. It is a genre, open to many kinds of artists with many different styles and purposes” (Higgins 1985:12). The main question that art historians have asked about artists books has been where, generically, does art end, and a book begin? The question was partially answered by Clive Philpott’s Venn diagram in the shape of a fruit salad (1982). Art was represented as an apple, and consequently book objects that fell into this category also fell to the genre of artists books. On the opposite end were books, represented as a pear, and thus literary works also became part of the artists books genre. In the middle, overlapping, and perhaps souring the possibility of clear delineations between books and art, was a lemon, which represented book art. The model has been rendered more complicated by the possibility of digital publishing, print on demand books, and more options for unique, multiples, large print runs, and digital editions, as illustrated by Kione Kochi (2014) and exhibited by Half Letter Press at the 2015 NY Art Book Fair. Artists books have been sought after, collected, and curated in exhibits. They have been commissioned and exhibited by museums, book art organizations, and private collectors. Above all, they are made to represent the work of artists through the book medium.

In one of my early films on the subject of dissent in the Soviet Union (Turning Back the Waves 2010), a librarian from Memorial—a non-governmental organization that documents political repression in the Soviet Union and Russia—displays scrolls of typewritten text typed on rice paper. The thin paper allowed several copies to be typed in a single pass, because several layers of claque could be placed between each sheet. These texts, which were officially forbidden, were clandestinely passed around between friends “for one night only,” which only added to their mystique. In the study of relics from the Soviet past, artist books take on another dimension altogether. Samizdat, a Russian abbreviation of sam-, self, and –izdat(el) – publisher, describes self-published underground books that existed outside of officially mandated literature throughout various Soviet epochs, but they became particularly popular during the late Soviet epoch during the Leonid Brezhnev era. The types of publications included banned literature, political pamphlets, censored poetry, and artists books. They were usually printed on home-made printing presses, or circulated as typewritten copies. For example, Dimitri Prigov, the same Moscow conceptualist poet who would host performative walking tours around his non-descript panel-home neighbourhood, would create meticulous typewriter art, something that would later be commemorated on a mural of the panel home in which he used to live. In an ironic subversion of the culturally profane (i.e. panel block apartment), and the sacred (i.e. poetry in Russian culture), the mural is currently threatened with demolition as part of the Moscow Renovation programme.

In studying the experience of Russian migrants living in panel homes in Berlin, as well as Moscow residents undergoing displacement at home, I propose to interview visual artists as we discuss those aspects of their panel home apartment that they would wish to represent, and to ask participants to paint these aspects using whatever preferred medium is at their disposal. The creation of each artwork will be documented using self-reportage, interviews, and written exchanges. Towards the end of the project, and in conversation with contributing artists, I will assemble these artworks into an artist book. Owing various state restrictions related to the Covid pandemic, many of us have spent long months at home, using interior spaces as a source of creative inspiration. The subject of painting the home will be a familiar one to those of us inclined to represent the world visually. As we work to recuperate a semblance of normal, social engagement with others, the experience of working on a collaborative art book about the home, and engaging with experiences of displacement at home and abroad, may be a productive way to reestablish a feeling of community amongst artists across different cultural contexts.

Almost a century ago, art educator Kimon Nikolaides argued that painting is a task that is processual, embodied, and based on having physical contact utilizing as many of the senses that can reach the eye at one time. I propose to create an artist book in collaboration with artists in Moscow and Berlin by using techniques that commemorate and interpret their lived experience of the home, and that resonate with sensory and collaborative methods of anthropological research. The research project will thus combine the theme of displacement with a visual representation of the home; an artistic language developed to engage with aesthetic qualities of panel–home lifestyles, domesticity, and urban experience, and to develop a creative way to disseminate anthropological research both as unique art object, and as published manuscript incorporating both voices and visual interpretations of panel homes by artists-participants. When the project gathers enough creative momentum, the artist book will be proposed to innovative publishers in anthropology and turned into an ethnographic text, widely distributed as a product of intercultural, artistic exchange documenting lived, embodied, and sensory experiences of the home.

Literature Cited

Becher, Bernd and Hilla Becher

1993 Gas Tanks. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Originally appeared under the title Gasbehälter, 1993, Schirmer/Mosel Verlag.

Gan, Gregory

2010b Turning Back the Waves. 96 minutes. Online access: https://vimeo.com/346322497

Higgins, Dick

1985 “A Preface” In Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook. Joan Lyons, ed. Layton, UT: Peregrine Smith Books. Pp 11-13.

Hoskins, Janet

1998 “Introduction” In Biographical Objects: How Things Tell the Stories of Peoples Lives. Pp. 1-25. New York: Routledge.

Kione Kochi

2014 “Clive Phillpot’s diagram updated to illustrate new complexities in the age of digital publishing.” Accessed online June 20, 2021: https://temporaryservices.org/served/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/KionePosterFruitWEB.jpg

Marks, Laura U.

2008 “Thinking Multisensory Culture” Paragraph 31:2 (2008), 123–137.

Moy Noviy Dom [My New Home]

2017 “The Program of Renovation of Residential Reserves in the City of Moscow” [In Russian: Programa renovatsii zhilishnogo fonda v gorode Moskve]. Moscow Municipal Decree No. 497PP from August 1, 2017. Pp. 1-17

Pimenov, Yuri

1968 New Residential Quarters. [In Russian: “Novie kvartali.”]. Moscow: Sovetskiy Khudozhnik.

Phillpot, Clive

1982 “Artists’ Books ‘Fruit Salad’ Diagram.” Accessed online June 20, 2021: https://monoskop.org/Artists_publishing#/media/File:Phillpot_Clive_1982_Artists_Books_Diagram.jpg

Tupitsyn, Margarita and Victor Tupitsyn, eds.

2017 Anti-Shows: APTART 1982-84. London: Afterall Books.